Weaponising Gas against the EU and Germany - Nord Stream 2

Spoilers: Even though Germany imports most of its energy from Russia, Russia is more dependent on Germany than vice versa. Nord Stream 2 (NS2) can be used by Russia to influence on German and EU policy making, The recently amended EU Gas Directive, EU competition Rules and the Energy Union are preventing Gazprom and Russia to abuse its market power and use it for political aims. These laws and rules are not carved in stone. Influencing the upcoming elections to the European Parliament can be a way for Russia to influence EU policies.

Questions have been raised about the Russian pipeline from Vyborg in Russia through the Baltic Sea to Greifswald in Germany. Critics argue that the project does not make any economic sense since there is no shortage of capacity in the existing Russian networks and demand is not high enough to warrant an expansion of the already existing network, (The Economist Feb 16th 2019). Still it seems to go through although delayed due to Denmark’s refusal to allow it to pass through its territory.

Based on the experience of Gazprom’s previous abuse of its market power, the EU has updated a directive which lays down the competition rules on EU soil. NS2 (read Gazprom) has already reacted and threaten to sue the European Commission. This kind of behaviour from Gazprom strengthen the critics' arguments that Nord Stream 2 is a political project aiming at weakening Ukraine and strengthening Russia's influence in the EU. It is claimed that by building NS2, Russia hopes to achieve three goals. Firstly, by bypassing Ukraine (and Poland and Slovakia), Russia can cut supplies to Ukraine without hurting Germany and put a halt to Ukrainian revenues of transit fees.[1] Secondly, NS2 provides Russia with more reasons to increase its military presence in the Baltic region, something that worries its Baltic neighbours and also Finland, Poland and Sweden. Thirdly, NS2 is feared to make the EU, and especially German, more dependent on Russian gas than today.

This post will deal with last of these arguments; the German dependence of Russian energy. I will also in this post make use of the WIOD database. Below I will analyse Russian energy exports as exports by the economic activities “Mining and Quarrying”, “Manufacture of coke and refined petroleum products”, “Electricity, Gas, Steam and Air Conditioning supply”.

This means that energy exporting industries use of services for exports are not included. The Service industries “Wholesale” and “Land transport and transport via pipelines” would be the obvious candidates to include. In 2014 they accounted for some 17% of Russian exports to Germany. Together with the three energy producing industries mentioned above, they accounted for some 83% of Russian exports to Germany. Therefore, the discussion below about the importance of energy exports for Russia underestimates the actual dependence. See the Annex at the end of this post for a brief discussion of what to include in energy exports.

The analysis below is based on the situation in 2014 since that it the last available year in the WIOD database. This means that the measures undertaken by Poland and the Baltic countries since 2014 to decrease their dependence on Russian energy, are not taken into account in the analyses. To be clear, you will not find any analyses of the effects of increased dependence of Russian energy in this post. I refrain to do that due to the assumptions I would have to do regarding technology and supply elasticities within and between industries in different countries.

Russia has inherited the Soviet energy dependence

To begin with, let us have a look at Russia’s dependence of oil. The developments of energy prices were important for the Soviet Union and are important for Russia today. Russian GDP measured in current dollars per capita follows oil price developments very closely, c.f. Figure 1.

Figure 1. Oil price and Russian GDP per capita 1992-2017.

Source: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2019/01/weodata/index.aspx

Plotting GDP per capita in constant prices or PPPs gives a similar, although not so strongly correlated, picture. Also, developments of government revenues and the exchange rate against the dollar shows the Russian dependence on oil. The dependence has been shown in many studies. Becker (2016) points out that changes in oil prices explain between half and two thirds of the variation in the growth of Russian GDP:

“In other words, a significant share of Russia’s macroeconomic volatility comes from oil prices so Russian economic policy makers are “hostage” to the international oil market to a very substantial degree when they make plans for their own economy. Of course, most modern, open economies are subject to external shocks, but the concentrated exports of a single set of commodities with very volatile prices makes the Russian situation particularly difficult.”

Germany is an important export destination for Russian energy exports.

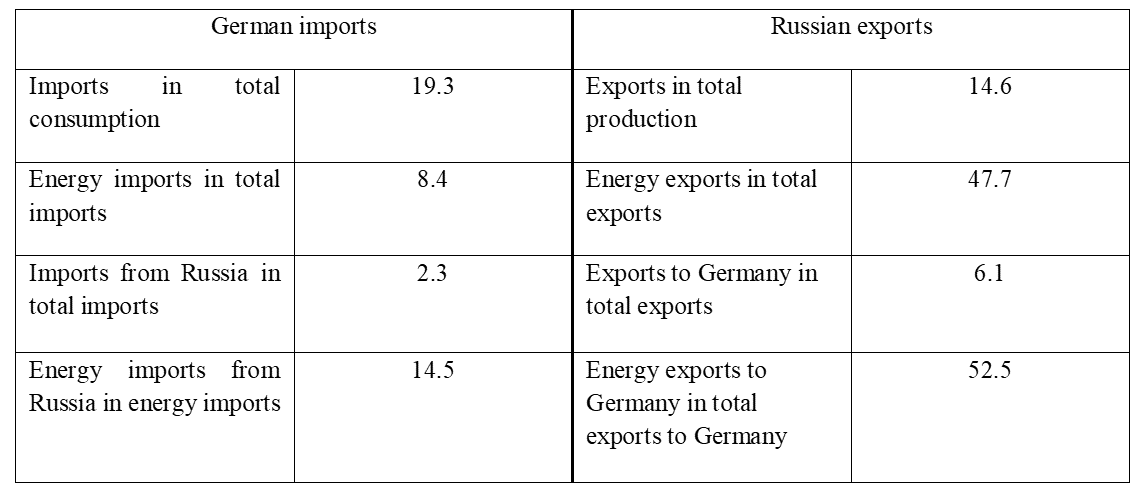

Since this post is primarily about the interdependence of Germany and Russia, an overview of German-Russian trade relations w.r.t. to energy is provided below. The overview concerns the situation in 2014 which is the latest available year in WIOD as mentioned above. Looking at the left part of the table shows that energy imports amount to around eight percent of total German imports out of which 14 percent is Russian energy. Total imports from Russian is only two percent of total German imports. Looking at the right part of Table 1 reveals that Germany seems to be more important for Russia than Russia is for Germany. More than half of Russian exports to Germany is energy and energy exports amount to slightly less than half of total Russian exports.

Table 1. German-Russian trade relations in 2014, (%).

Source: The WIOD database, www.wiod.org. ROW denotes Rest of the World.

Also, more recent data confirm the importance of the German market for Russia. The Netherlands, China and Germany were the three largest destination market for Russian exports in 2015 and 2016. Even though it is difficult to compare different sources it may be the case that Germany’s reliance on Russia as an energy source has increased since 2014. In the first semester of 2018, some 25-50% of German Extra-EU imports of petroleum oil originated in Russia and the equivalent share for natural gas was 50-75%.

The Russian economy is more dependent on Germany than vice versa

Interdependence w.r.t. to trade relations between different countries can be analysed in many ways. As in previous posts I will analyse the dependency with two indicators: Trade in Value Added (TiVA) and Value Added in Trade (VAiT). See Stehrer (2013) for a clear exposition of the two indicators.

The first of these indicators can be used in two ways. The first way is to calculate the Russian share of the value of domestic final consumption in other countries. This provides an indication of the importance of Russian final goods for different countries to satisfy final demand. The second way to use the indicator is to calculate how much value added is created in Russia due to final consumption in other countries. The result can be divided by Russian GDP in order to have an indication of the importance of foreign final consumption for Russia.

Beginning with the first way to measure the interdependence, the largest Russian shares of final domestic demand are found in Baltic and East European countries. The largest share of final domestic demand in any country is found for Lithuania: 3.5%. Russian shares of Cyprus final domestic demand are also relatively high. Most of that refers to domestic absorption of financial services reflecting financial flows from Russia to Cyprus and further. Russian shares of final domestic demand in its three largest export markets, China, Germany and The Netherlands, only amount to around some 0.5% of the values of total domestic final consumption in those countries, c.f. Figure 2.

Figure 2. Russian shares of final domestic demand in different countries in 2014 (%).

Source: The WIOD database, www.wiod.org. ROW denotes Rest of the World.

The corresponding German share of the value of total final domestic consumption in Russia amounted to 1.3% in 2014. That is twice as much as the Russian share of German domestic consumption which indicates that Germany is relatively more important for Russia than the other way around.

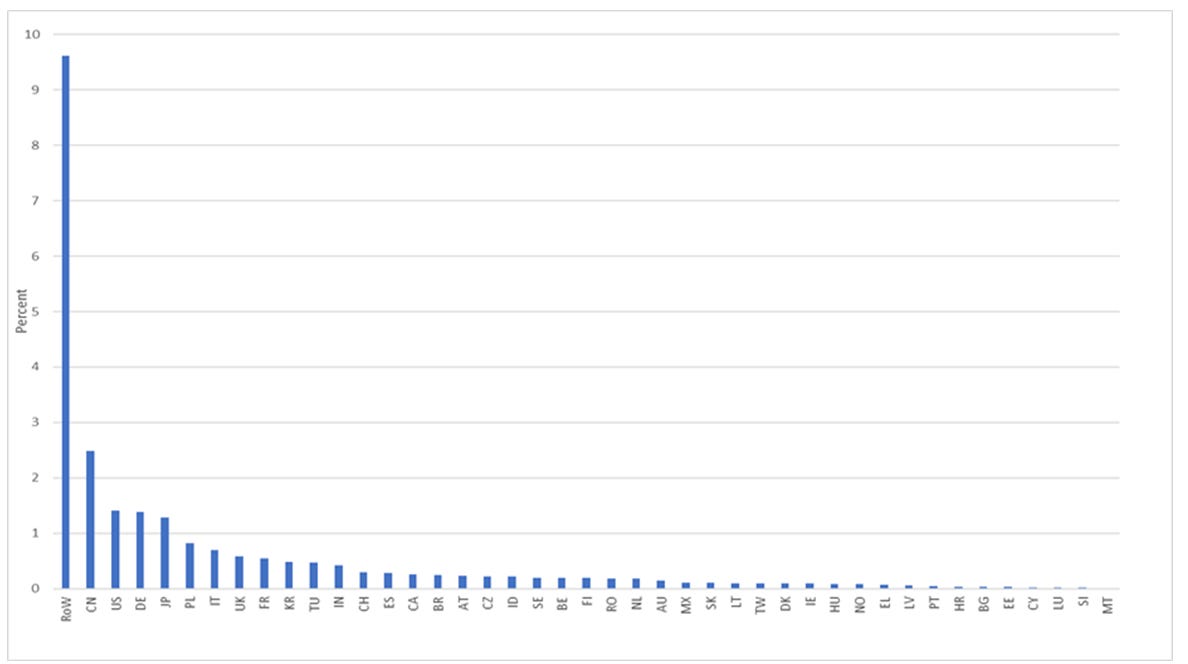

Using the indicator the other way shows that most value added, as a share in GDP, is created due to final consumption in the large aggregate Rest of the World. Also, final consumption in China, USA, Germany and Japan appear relatively important in generating Russian value added. Russian value added generated due to final consumption in these countries’ domestic markets and their value added exports amount to 2.5%, 1.4% and 1.4% respectively in Russian GDP, c.f. Figure 3.

Figure 3. Russian value added as shares in Russian GDP due to final consumption in other countries in 2014 (%).

Source: The WIOD database, www.wiod.org. ROW denotes Rest of the World.

Flipping the coin also this time shows that only 0.5% of German GDP was created due to Russian final consumption and value added exports in 2014. This means that variations in Russian GDP have smaller impacts on Germany than the other way around.

Russian value added shares in total German gross exports are relatively low

The second indicator VAiT, shows the extent to which Russian intermediates are used in gross (intermediates and final goods) exports of other countries. The “extent” is measured as Russian shares in total value added of gross exports from other countries. Baltic, Finnish, Cypriot and Eastern European firms use relatively more of Russian intermediates than other countries in their exports. German firms use a bit less than the average, c.f. Figure 4.

Figure 4. Russian value added content shares in other countries’ exports in 2014 (%).

Source: The WIOD database, www.wiod.org. ROW denotes Rest of the World.

And consists mainly of energy which is used by German energy-intensive industries

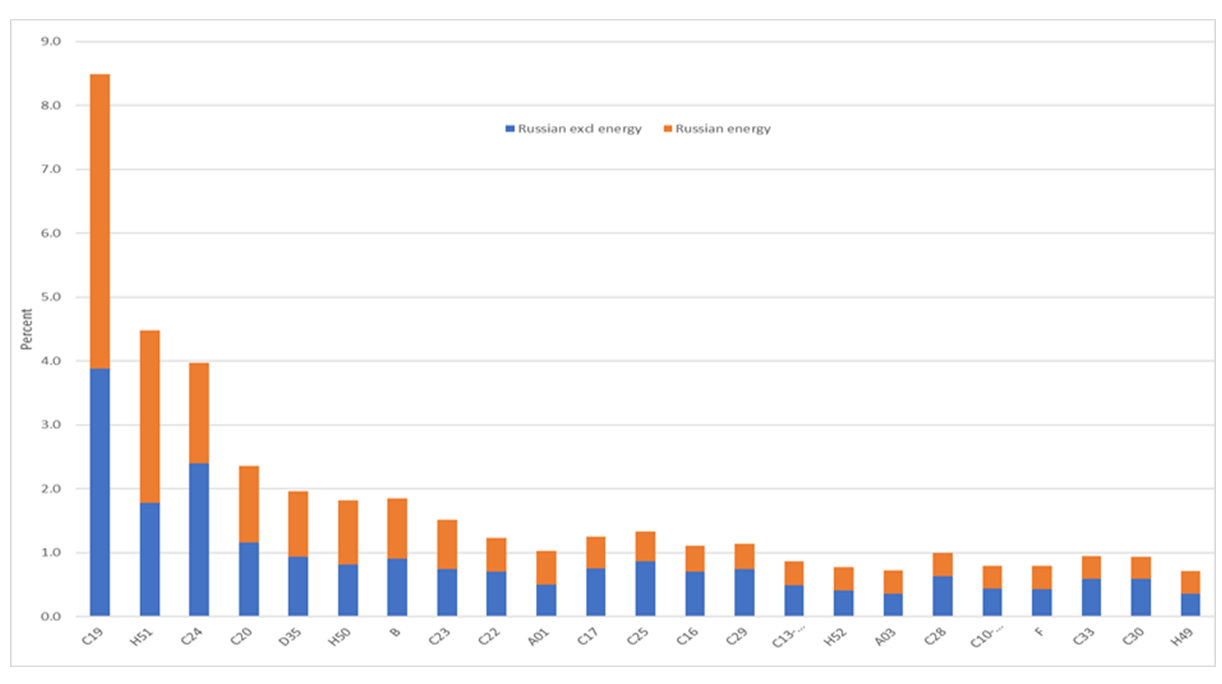

The values per country can be broken down by industry. That makes it possible to analyse in which markets, by country and product (industry), where Russian gross exports are used. Focusing on Germany, it is no surprise that Russian value added content shares are relatively high in energy intensive industries such as “Manufacture of Coke and refined petroleum products” (C19), “Basic Metals” (C24) and “Air Transport” (H51), c.f. Figure 5.

Figure 5. Foreign and Russian value added content shares in German industry exports in 2014(%).

Source: The WIOD database, www.wiod.org. ROW denotes Rest of the World.

And also much of the Russian non-energy products are energy-related

The high energy content in the Russian supply is confirmed if one breaks down Russian value added content shares into shares related to energy production and non-energy production respectively. And most of the non-energy Russian shares are actually energy-related as the use of energy also requires services industries such as Wholesale, Transportation and Storage, c.f. Figure 6.

Figure 6. Russian and Russian energy industry value added content shares in German industries’ exports in 2014(%).

Source: The WIOD database, www.wiod.org. ROW denotes Rest of the World.

Russian attempts to increase its influence through political allies

In this post I have shown that Russia is more dependent on Germany than the other way around. This is a problem for an autocratic regime such as Russia that attempts to influence policy making in other countries and especially the EU. NS2 is a way to increase the German dependence on Russia. The EU's Energy Union, the Gas Directive and competition rules are hindering these ambitions for now. But by offering lower prices than now, assuming that abolition of transfer fees to Poland and Ukraine outweigh construction and transportation costs for NS2, and increase sales in the short run, Russia can EU industries more dependent in the future. The increased dependency could then be used in order to achieve political goals.

The reaction of NS2 (Gazprom) to the amended Gas Directive shows that Gazprom is as uncomfortable today with EU competition laws as Gazprom was yesterday when the EU Commission put an end to its unfair trade practices and abuse of market power. Russia has invested both money and resources in building alliances with political parties such as Front National in France, FPÖ in Austria, Jobbik in Hungary and Lega Nord in Italy not to mention those even further to the right [Shekhovtsov (2017)]. Since Russia has tried to influence elections in many countries, the EU Commission has put forward an Action Plan against Disinformation. Whether this will prevent Russia from interfering with the elections to the European Parliament in order to increase its influence remains to be seen. But if Russia does indeed manage to increase its leverage on EU politics, we will see changes in the Competition laws and a dismantling of the Energy Union.

Read more:

Assenova, M. (2018). “Europe and Nord Stream 2. Myths, reality and the way forward”. Center for European Policy Analysis. https://www.cepa.org/europe-and-nord-stream-2

Becker, T. (2016). “Russia’s Oil Dependence and the EU”. Stockholm Institute of Transition Economics. Working Paper No. 38.

European Commission. "Energy strategy and energy union". https://ec.europa.eu/energy/en/topics/energy-strategy-and-energy-union

Pöyry Managemant Consulting (2016). “A well-functioning EU gas market.

The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (2018). “Russian gas transit through Ukraine after 2019: the options”. University of Oxford. https://www.oxfordenergy.org/publications/russian-gas-transit-ukraine-2019-options/

Warsaw Institute (2018). “Ukraine-Nord Stream 2: Struggle over Gas Transit”. Warsaw Institute, special report. https://warsawinstitute.org/ukraine-nord-stream-2-struggle-gas-transit/

Rossbach, N. H. (2018). “The Geopolitics of Russian Energy. Gas, oil and the energy security of tomorrow”. FOI, https://www.foi.se/rapportsammanfattning?reportNo=FOI-R--4623--SE

Shekhovtsov, A. (2017). "Russia and the Western Far Right". Routledge

Notes

[1] Ukraine has made itself independent or at least significantly reduced its dependence of Russian gas since Russia attacked Ukraine in 2014.

Annex . Russia trade with energy, what to include.

Russian exports of energy products also require the use of services to sell, transport, maintain, store and other activities necessary to deliver energy to external markets. The WIOD database also includes trade in services, which would facilitate analysis that take the importance of services into account.

The WIOD database contains data for industries on the 2-digit level for ISIC 4/NACE Rev. 2. The economic activities that are relevant for analysing Russian energy exports are classified as “Mining and Quarrying”, “Manufacture of coke and refined petroleum products”, “Electricity, Gas, Steam and Air Conditioning supply”, “Wholesale trade, except of motor vehicles and motorcycles” and “Transportation and Storage”. While the three first industries definitely qualify in analyses of Russian energy exports, the service industries Wholesale and Transportation encompass a number of activities unrelated to energy. Including those would therefore overestimate Russian exports.

It is difficult to estimate (sic!) the overestimation. Some information about the relationship between energy producing industries and service industries can be derived from input-output tables. The Electricity and Refined Petroleum (D35 and C19) have rather high output multipliers, 2.35 and 2.21 respectively while Mining Industries is lower; 1.58. Decomposing these multipliers into the effects on the different industries show that increases of demand for these three industries products have the largest effect on Wholesale (G46) which includes services related to energy sales. Also, services industries Land Transport and transport via pipelines (H49) are strongly complementary to the energy producing industries, especially to Refined Petroleum industries.