Is there food greedflation in Sweden?

Spoiler: The inflation rate in Sweden is both increasing and decreasing depending on which price index is used. Three measures are regularly published by Statistics Sweden: KPIF-XE which excludes energy prices, KPIF, in which households’ interest rates on loans for housing are held constant. In KPI, energy prices are included, and interest rate changes are allowed to vary.

Inflation excluding energy keeps increasing because of increasing food prices. Prices of food make up for the second largest share in consumption. Food and beverages are sold on markets with barriers to entry hampering competition. The increasing inflation of food makes people wonder if the incumbent firms take advantage of their market power to increase their profits. That is not as straightforward as many seem to think. Demands for price caps on food have been raised lately. That would lead to shortages and weaker competition.

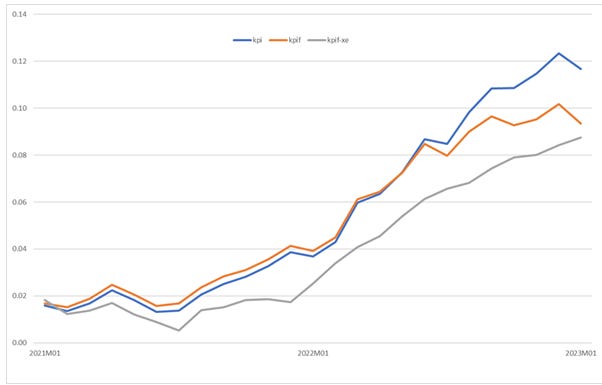

The last update from Statistics Sweden showed that inflation is both increasing and decreasing. While energy prices and housing costs tend to slow down, inflation rates of other prices keep increasing as the price index KPIF-XE shows, c.f. Figure 1.

Figure 1. Annual average inflation rates 2021:1-2023:1.

Source: Statistics Sweden, https://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/en/ssd/ Note: KPIF-XE excludes energy prices. In KPIF, are households’ interest rates on loans for housing held constant. In KPI, interest rate changes are allowed to vary.

Food prices

Due to constrained supply chains following the Covid pandemic, inflation increased globally. Supply chains are however becoming more lax which after some time should be reflected in lower inflation, if not prices. Since January last year, contributions to total inflation of goods excluding foodstuff, services and foodstuff increased, c.f. Figure 2.

Figure 2. Contributions to the inflation in the KPIF index.

Source: Sveriges Riksbank February 2023, The monetary policy report. https://www.riksbank.se/en-gb/monetary-policy/monetary-policy-report/2023/monetary-policy-report-february-2023/

The impact of increases of food prices have has grown and is expected to increase further for at least the year to come. For 2023, the Riksbank forecasts food prices to increase more than prices of other goods and prices of energy and prices of services. Adding to this inflation is the depreciating SEK. Import prices of food are highly correlated with the exchange rate, c.f. Figure 3.

Figure 3. Import price index and the SEK/USD exchange rate.

Source: Statistics Sweden, https://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/en/ssd/ Riksbanken (the National bank of Sweden), https://www.riksbank.se/en-gb/statistics/search-interest--exchange-rates/ Note: The import price index measures the price developments of imported food in Sweden.

Prices change in response to changes in supply and demand. The Covid crisis resulted in disrupted supply chains giving rise to large increases of prices of raw material and food prices. Price increases due to disruptions in supply chains is not a sign of weak competition. There will be price increases in markets characterised by perfect competition as well as in oligopolistic markets. During the Covid crises, there were also large shifts in demand which led to increased prices of the goods and services of for example construction goods and electronic devices. Disentangling the demand and supply effects is no easy task. And the task is complicated by the fact that many prices are fixed for long periods due to contracts between suppliers and consumers. This means that price developments in a given period of time may be the response in prices to increases in costs during the contractual period.

Food prices and profits

This development has triggered a discussion about greedflation in food prices, i.e., whether retail shops and food producers increase prices in “excess” of their increasing costs. If they do, their profit margins and profit shares would increase.

There are very few new things under the Sun. Greedflation is just a new concept used to describe an old phenomenon. Food producers and owners of retail shops set their prices as markups over marginal costs. The markup, or their ability to pass on costs, depends on how fierce the competition on their markets is. Therefore, price movements alone cannot be used as evidence of greedflation. One needs to look at developments of profit margins and profit shares.

The Swedish National Institute of Economic Research (NIER) has analysed the effects of increasing prices in the Swedish industry. The analyses are made for different aggregates of industries. They analysed two measures of profits, profit margins and profit shares.

A firm’s profits equal its revenues minus costs. Costs include both wages and input costs such as energy and materials. (I’ll ignore capital as I only discuss short-term developments, so I make no distinction between gross and net operating surplus, and I will also ignore profits measured as return on capital). The profit margin is calculated as profits divided by the value of production. A firm’s profit share equals profits divided by value added. The value added is revenues (the value of production) minus input costs. Since value added is smaller than revenues, the profit share is larger than the profit margin.

That also means that the increase of prices needed to keep profit shares constant, is smaller than the increase of prices needed to keep profit margins constant when input costs increase. As NIER shows here, a price increase of the same amount of the cost increase will keep a firm’s profit share constant, while a price increase in excess of the cost increase is needed to keep profit margins constant.

They have a nice example showing this which I replicate below.

A bakery produces 200 loaves of bread at the price of SEK 45 per loaf. The bread is produced by two bakers which costs SEK 2,000 each per day. Butter, water, eggs, energy and other inputs costs SEK 2,000 per day. The example is price and costs per loaf of bread.

Price: 45

Input costs: 10

Labour costs: 20

Profit: 45 – 10 – 20 = 15

Value added: 45 – 10 = 35

Profit margin: 15/45 = 0,33 or 33%

Profit share: 15/35 = 0,43 or 43%

What happens when input costs increase by 100%, from SEK 10 to SEK 20 per loaf of bread?

As you can find out yourself by plugging in new input costs, to keep the profit margin constant, the price needs to increase by more than input costs, to at least SEK 60 per loaf of bread, but to keep the the profit share constant, the price only needs to increase by the same amount as input costs increase, to SEK 55 per loaf of bread.

Looking at actual developments, it seems as profit shares for the food industry have been higher than the average since the turn of the Millennium. There are however substantial variations from quarter to quarter, c.f. Figure 4.

Figure 4. Quarterly profit share developments for food industries 2000:1—2022:4.

Source: Swedish National Institute of Economic Research, https://www.konj.se/publikationer/specialstudier/specialstudier/2022-12-06-konsumentpriserna-har-inte-okat-mer-an-vad-som-kan-motiveras-av-okade-kostnader---indikerar-modellberakningar.html. Note: The thick green line shows the average share and the dashed lines the average plus and minus one standard deviation.

Unfortunately, NIER, and Statistics Sweden, doesn’t publish profit shares for food stores so I don’t know how their profit shares have developed. There is only anecdotal evidence or limited surveys on price developments, nothing on input costs. Statistics on food prices increasing more than in other countries is less informative than what you might think since the SEK has depreciated against most major currencies.

Weak competition on the food markets

What matters more is the degree of competition on the markets, especially the competition between different food retail stores. The Swedish market is characterised by a high degree of market concentration. It is dominated by three large firms. ICA, Axfood, and Coop make up for around 85% of the market with ICA occupying the largest share of 50%. The establishemt of foreign retail firms during recent years has not had any significant effects on the competition.

The competition on Swedish market has historically been weak. This is to a large extent explained by regulatory barriers preventing new firms to enter the market. Swedish municipalities have monopoly on zoning planning. They decide both on whether new establishments can come about and the locations of the new establishments. The location of new retail stores is crucial for the competition. Access to shops in the proximity of consumers’ homes, workplaces or their children’s kindergartens, save a lot of time for time constrained households. Retail stores with favourable locations can therefore use this to set prices enabling relatively high profits. Planning and construction of new areas in a municipality concerns not only decisions about housing but also about the establishment of shopping centres. You can’t find a newly constructed shopping centre in Sweden where there isn’t an ICA store.

Faced with the media attention of increasing prices of food, the government has commissioned the Swedish Competition Authority to conduct to analyse the competition on markets for food. This is not the first time that those markets are analysed. To my surprise, the Competition Authority in 2018 in their analysis concluded that:

“In summary, it is the overall assessment of the Swedish Competition Authority that competition in the food supply chain is well functioning and that consumers have sufficient tools at hand making active, well-informed choices.”

Nine years earlier, the Competition Authority published two analyses concluding that the competition on the markets were weak, one here, and the other one here. I’m curious to find out what the conclusions will be this time.

Why price caps are terrible.

The increasing food prices have triggered a debate and demands for price caps on food. This is an extremely bad idea. As we know, price caps create shortages and rationing. Price caps also provide incentives for firms to lower the quality of goods since they cannot cover their increasing costs at the fixed price. Lowering the quality can be done in many ways, by substituting cheaper and low-quality inputs for more expensive and high-quality inputs, by reducing the amount of food in cans and packages and reducing both the amount of food and sizes of cans and packages.

Price caps are also detrimental for the competition on the markets. A price cap at increasing costs mean that many firms will not be able to cover their costs. They will therefore leave the market. This means that there will be both fewer varieties of goods and fewer goods of the same variety. This will mostly hurt foreign and small domestic suppliers. The incumbent firms within the food industry and retail stores are in better positions to use economies of scale to cover the costs at the prevailing price cap. They, and also, the existing retail stores are also in better positions to use their bargaining powers against suppliers in negotiations of inputs and their costs. The result will be fewer goods, fewer firms, and weaker competition on the markets.