Is the Belt and Road Initiative a blessing or a trap?

Spoiler: The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is often described as blessing for the countries that are part of it. The BRI is supposed to increase trade and growth. China provides the funding, the expertise and often much of the labour force.

But it might be a good idea to ask why China wants to pursue these infrastructure project when other international lenders don’t. There is no shortage of global capital, on the contrary. Infrastructure projects are long term and often yield low returns. Low and uncertain returns in the far future in combination with very high capital costs scare most lenders away.

But Chinese lenders seem willing to take on high risks. The reason Chinese lenders undertake projects that may not be profitable is that they can call Beijing to pick up the tab. And Beijing can put pressure on the borrowers.

China claims that the Belt and Road Initiative’s infrastructure projects will boost trade and growth..

The BRI can be regarded as an alternative for the Chinese to hold low-yielding US bonds. That means that they expect the returns from BRI to be higher. And according to official Chinese web pages there are no limits to the benefits of the BRI. It is also easy to find other web pages and articles about its benefits. I’ve read a lot of articles and reports about the BRI, and its effects on global trade and growth. When reading these, one question kept popping up; Why haven’t at least some of these projects already been undertaken and why are only Chinese lenders funding these projects?

…but why haven’t all these infrastructure projects already been undertaken?

Having asked that question I asked myself another one; if other lenders don’t think the projects will be profitable, why are Chinese lenders willing to take such high risks? To my relief, this question has been raised by people far more knowledgeable than me. Christopher Balding and David Dollar are among people who have studies this. They find that the Chinese lenders are either more risk-taking, or at that they under-price risk. It can’t be stated clearer than this by Christopher Balding:

“China is willing to accept levels of risk that others are not. Many see investors not funding projects and assume that there are no funds available for projects in countries like Pakistan, Cambodia, and Kenya from non-Chinese investors. There is enormous amounts of capital available but that does not mean that those investors are willing to accept the level of risk that China is.”

When projects fail and borrowers can’t pay, Chinese banks call Beijing

And many of these projects like the railway in Kenya turn out to be white elephants which means that it is an asset that costs a lot of money and is difficult to get rid of. And the airport in Zambia is another white elephant. The airport is generating massive losses increasing Zambia’s already very large foreign debts. And just like in Kenya and Sri Lanka , the Chinese banks call Beijing, when the borrower defaults. And Beijing puts pressure on the borrowing countries’ governments and take over the ports, airports and railways.

And in many countries, corruption is pervasive and rule of law absent

There are other advantages that Chinese can offer. Normally, before large infrastructure projects are undertaken, borrowers and lenders are careful and require transparent bidding for contracts involving as many as possible in order to get the best value for money. They also carry out economic and environmental impact assessments. This will delay the projects and make it difficult to collect bribes.

That’s why China is the preferable option for corrupt regimes. Chinese firms don’t care about financial transparency, competitive bidding for contracts, environmental reports and other considerations that are standard in countries characterised by rule of law. This way of doing business has fuelled corruption while allowing governments to burden their countries with unpayable debts. In some countries, like Malaysia, the shady business model associated with Chinese money has led to tough political battles and Xi Jinping’s portrait even turned up on political billboards during an election campaign. Concerns of the corruption have also been raised in Kenya, Maldives, Pakistan, Uganda and Zambia.

And why is low productive Chinese construction firms (almost) always used?

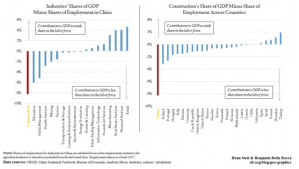

I didn’t need to ask myself if Chinese lenders had access to more efficient construction firms than other countries. There was no need to. Chinese growth has required much more investments than for example, Japan, Poland and South Korea, so arguing that Chinese production would be more efficient than production by other countries, would be just wrong. The relatively lower efficiency of Chinese production is also reflected in the relative lower (and declining) total factor productivity growth rates. And my beliefs were confirmed by Steil and Della Rocca (2019) who show that the construction industry is China’s least productive industry, c.f. Figure 1.

Figure 1. Chinese construction industry’s productivity compared to other Chinese industries (left) and other countries’ construction industries (right).

Not only is the Chinese construction industry less productive than other Chinese industries, it is also much less productive than construction industries in the OECD. This means that it would be much wiser for Chinese lenders of infrastructure projects to use construction firms from other countries. In fact, it would probably have been better to use foreign firms for the construction of high speed railways in China. But probably better not to build them at all. And as witnessed in for example Zambia, the roads are just awful.

Chinese lenders still prefer to use Chinese firms and labour. There have been complaints, in some countries where BRI projects are undertaken, about bringing in Chinese labour instead of local. And as in Zambia Chinese projects are often more expensive and of lower quality than other projects.

Chinese lending should only be used in competitive biddings for infrastructure with full transparency...

I’m not saying that Chinese-financed and Chinese-led projects never can be beneficial. I’m saying that the proof of the pudding is in the eating. Assuming that a bidding for an infrastructure project is competitive and undertaken under full transparency with accompanying assessments, the project should be undertaken also if its financed by Chinese money and undertaken by Chinese firms. According to an analysis by the World Bank, BRI transport project could increase world trade between 1.7 and 6.2 percent and global income by 0.7 to 2.9 percent. However, the benefits are conditioned on implementation, in China and countries where the projects are undertaken, of policy reforms that increase transparency, expand trade, improve debt sustainability, and mitigate environmental, social, and corruption risks. A major reason these projects have not been considered as profitable outside China is the implied mal functionings of markets in these countries.

And the authors of the World Bank report emphasise that the benefits, mentioned above, come with risks debt sustainability (for heavily indebted countries), governance risks (the less transparency, the higher is the risk of corruption) and environmental risks (carbon dioxide emissions will increase heavily in some countries where environmental assessments are rare)

...but not if you object to lending money from a government that kidnaps other countries’ citizens, uses its firms to spy on other countries and locks up members of a minority population in prison camps

Though the Chinese communist regime has abandoned mass murderer Mao’s disastrous economic policy, it shares Mao’s regime’s contempt of human rights. One well-known example is the kidnapping of the Swedish publisher Gua Minhai in Thailand. His case is well described by his daughter here who campaigns for his release. As if the kidnapping of a Swedish citizen wasn’t bad enough, the communist regime has attacked Swedish media, well-known authors, the Swedish branch of the international organisation for free speech, and members of the Swedish government who awarded Gua Minhai this year’s Tucholsky prize.[1] The behaviour of the Chinese ambassador has raised more than one pair of eyebrows over the world. In an interview with Swedish Radio, the ambassador talking about critics said: "We serve our friends nice wine and our enemies weapons".

This is a good place as any for a furry "animal".

The kidnapping of Gua Minhai was in no way unique as witnessed among others by this former Chinese spy. The interview with Mr Wang represents another confirmation of the close relationship between the Chinese intelligence services and Chinese firms that has raised concerns in many countries. According to Chinese laws, Chinese firms are obliged to cooperate with Chinese intelligence firms when so required which is why for example Huawei has become under scrutiny not only in USA but in many other countries too.

And should we use equipment from the same producer who also supplies the prison camps where around a million members of the Uighur population is imprisoned?

And these are ingredients of the model that Xi Jinping wants to spread over the world either by soft power or by infiltration

Chinese ambitions are far-reaching. Beginning with Africa, Xi Jinping wants to enhance China’s soft power to spread China’s authoritarian model over the world. Outside of already authoritarian-ruled countries, China’s model is unattractive and much less powerful than democracies’ soft power. And this is perhaps why the Chinese regime uses other methods in democratic countries , especially in those with already large Chinese expat populations such as Australia.

Read more:

Christopher Balding’s blog: https://www.baldingsworld.com/

A Swedish blog on China http://inbeijing.se/bulletin/

The Economist:

https://www.economist.com/china/2019/10/24/to-suppress-news-of-xinjiangs-gulag-china-threatens-uighurs-abroad

https://www.economist.com/china/2019/10/03/xis-embrace-of-false-history-and-fearsome-weapons-is-worrying

Foreign Policy: https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/12/11/cotton-china-uighur-labor-xinjiang-new-slavery/

International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, www.icij.org

[1] The prize is awarded each year to an author or publisher who is under attack from authoritarian regimes.