Income inequality in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

Income inequalities are among the highest in the EU countries even though labour shares have increased, and real wages have outgrown labour productivity.

Spoiler: My previous post about the three Baltic countries was about declining productivity growth rates. In this post I will look at income inequalities in the three Baltic countries. Income inequalities in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania are high. Gini coefficients for income are among the highest in the EU in 2023.

Declining productivity growth rates have in some countries been accompanied by lower labour income shares in GDP, and decouplings of real wage growth from labour productivity growth. This has not occurred in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Income inequalities in Estonia, and Latvia have not increased for more than ten years. The Lithuanian income inequality has increased slightly. It is now the second highest in the EU measured by the Gini coefficient. Poverty rates are declining in all countries.

High income inequalities

Income inequalities are high in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Income inequality in Estonia has decreased since 2014. That year, it was the highest in the EU with a Gini coeffecient of 35.6. Income inequality in Latvia, and Lithuania were the second and fourth highest respectively, showing Gini coefficents of 35.5, and 35.0 respectively. Since then, income inequalities have decreased in Estonia, and Latvia by 3.8 and 1.5 points respectively while it increased by 0.7 in Lithuania. Income inequality in Lithuania is now higher than in Estonia, and Latvia.

GINI coefficients in EU in 2023.

Source: European Commission, Eurostat. Note: Gini coefficents for equivvalised households’ disposble incomes.

This development is confirmed by data on the P90/P10 income decile ratios from OECD. In 2013 the 90th percentile households earned 5.3 more than the 10th percentile households. The ratio decreased slightly to 5.0 in 2021 and was at that time lower than in Latvia, and Lithuania.

P90/P10 income decile ratios in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

Source: OECD. Note: Income decile ratios for equivvalised households’ disposble incomes.

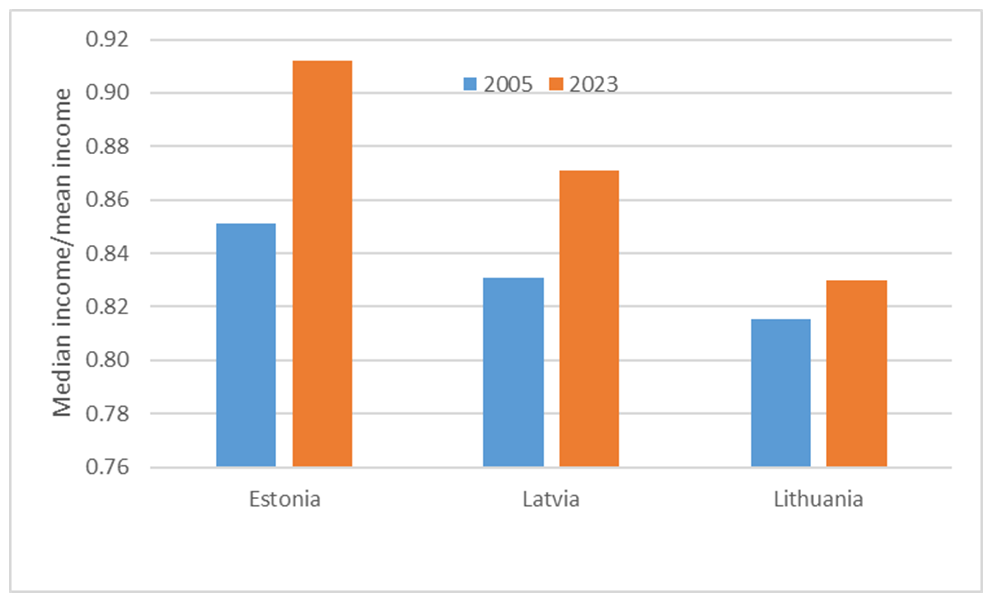

The ratios of median to mean equivalised households’ incomes confirm the above presented developments. The ratios have decreased in Estonia, and Latvia but increased in Lithuania between 2005 and 2023.

Median to mean equivalised net household incomes in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

Source: European Commission, Eurostat. Note: Equivvalised households’ disposble incomes.

Below, I will look at another and more narrow measure of income inequality, the labour share of income. I will also show how real wages have developed relative to labour productivity.

Discrepancies between these measures and the Gini and others, can therefore be due to divergencies in total incomes caused by high returns on capital, and lower transfers such as pensions and other benefits.

Anyway, economic theory tells us that there should be a close relationship between real wages and labour productivity as I wrote in this post.

Decreased inequality between capital and labour

In all three countries did real wage growth exceed labour productivity growth as shown below together with labour shares in GDP.

Economic theory also predicts that the labour and capital shares in GDP should be relatively stable over time. The problem with that prediction is that it is valid when the economy is in its long run equilibrium. And that can not be translated into a certain number of years. So, labour shares vary somewhat over time. In fact it has increased in all three countries. Note that the shares are measured in the vertical right axes. In Estonia, the labour share increased slightly from 61% to 63% while the increases in Latvia and Lithuania were significantly higher, from 55% to 67%, and from 52% to 61% respectively. Also, the labour shares in GDPs increased.

Increasing labour share and real wage growth in excess over labour productivity growth in Estonia.

Source: Ameco Database, DG Ecfin, European Commission. Note: The labour share in GDP is adjusted for imputed compensation of self-employed.

Increasing labour share and real wage growth in excess over labour productivity growth in Latvia.

Source: Ameco Database, DG Ecfin, European Commission. Note: The labour share in GDP is adjusted for imputed compensation of self-employed.

Increasing labour share and real wage growth in excess over labour productivity growth in Lithuania.

Source: Ameco Database, DG Ecfin, European Commission. Note: The labour share in GDP is adjusted for imputed compensation of self-employed.

The high increases of labour shares in Latvia and Lithuania might be adjustments to more “normal” levels. The EU average labour shares in 1995 and 2023 amounted to 64% and 63% respectively.

The capital stock in the three countries as in other parts of the useless Soviet Union were old, worn and torn and inadequate. Domestic savings were too low to build a new capital stock, but large inflows of capital. At the same time, there were outflows of labour to other EU countries. These flows tend to increase capital intensities of labour and result in rising real wages.

I have above, used average hourly real wages. Most studies look at median hourly wages. I do not have access to those for the above time period. It could be that wage inequalities have incresed in the three countries. But I haven’t seen that in the developments of households’ incomes out of which wages make up the largest shares.

To make a better analysis of the sources of income inequalities in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, I would need data on all sources of households incomes for longer periods of time.

Disposable incomes grow faster than in the EU and poverty rates are falling.

Meanwhile, here are a few other indicators from Eurostat’s social scoreboard. Employment rates are high, especially in Estonia where also unemployment rates are equal to or lower (long term) than in the other countries and the EU average.

Labour market indicators for Estonia (light blue), Latvia (yellowish), Lithuania (green), and EU (dark blue).

Source: European Commission, Eurostat.

Disposable household incomes have grown faster in all three Baltic countries than in the EU. Poverty rates have fallen significantly, especially in Latvia, and Lithuania but are still far above the EU averages. However, poverty rates for children are lower.

Income and poverty indicators for Estonia (light blue), Latvia (yellowish), Lithuania (green), and EU (dark blue).

Source: European Commission, Eurostat.

Is the glass half full or half empty?

So far I have managed to confuse myself with the indicators above. You can look at the developments from at least two different points of view. The glass is either half full or half empty.

The first view would present the results like this: Increasing labour shares and real wages growing more than labour productivity have led to higher incomes, lower unemployment, and decreased poverty rates.

The second view would present the results like this: Despite increasing labour shares, and real wages growing more than labour productivity, income inequalities and poverty rates are still among the highest in the EU.