Spoiler: Today, the 10 December, is the day the prize ceremony for the winners of the Nobel Prize and the Economics Prize. The latter is not a Nobel Prize even if people carelessly denote it as such. Here is the story of it on the Nobel Prize Foundation’s website. I have been rambling about institutions and prosperity on this blog several times. Below are some graphs where I try to show the relationship between different indicators of the quality of instituions and prosperity. My graphs are mere correlations, the winners of this year’s prize have undertaken a series of economtric analyses taking the interrelationships between institutions and prosperity into account.

Here is the popular version explaining Acemoglu’s, Johnson’s, and Robinson’s work. It is essentially about explaining income differences between countries. They focus on the role of institutions for growth and prosperity. They also explain why differences in institutions persist and how institutions can change. Autocracies can be beneficial for growth, for example when growth comes from extracting natural resources. If the natural resources are located in autocracy, the elite or state does not have to care about property rights, effects on the environment or labour conditions. In such a case, they have no incentive to alter the institutions.

Below are some graphs from my previous posts about institutions and prosperity. The first graph shows that stable autocracies tend to be poor while the opposite applies for stable democracies. In some cases, increases of GDP per capita from 1990 to 2022 were accompanied by transformations from autocracies to democracies.

Democracies are more prosperous than autocracies

Source: World Bank (GDP per capita and Varieties of Democracy Note: Outliers such as Ireland, Qatar, Luxembourg, and Singapore were omitted.

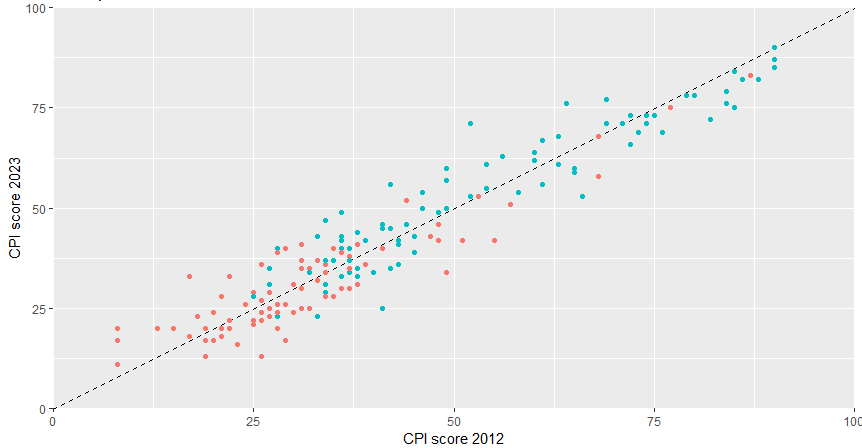

Countries with poor institutions are often autocracies. The quality of institutions affect people’s behaviour and economic transaction between firms, household and the government. This becomes particularly obvious when it comes to corruption. Corruption is usually stronger in autocracies.

Corruption is weaker in democracies

Source: Transparency International and Varieties of Democracy

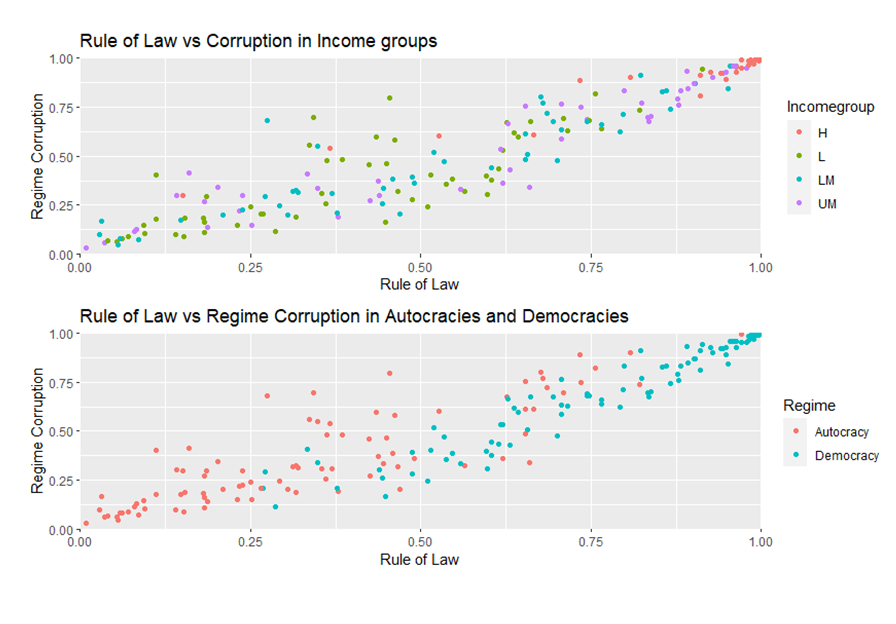

Rule of Law tends to be stronger in democracies. We should therefore expect weak corruption and strong rule of law to be correlated across countries. I tried to show this in a previous post where I also divided countries into the World Bank’s categories of income groups.

Below are two graphs from a that post:

where I also discuss some criticism of the positive relationships between institutions and prosperity. In the two paragraphs below, I try to show that democracies both are more prosperous and have better institutions.

Whatever causality relationship, countries which have become democratic have often reformed and designed institutions that strengthen Rule of Law and weaken Corruption. While the quality of such institutions in general are higher in democracies, they can also be found in prosperous autocracies. Conditions of Rule of Law a Control of Corruption are related with prosperity as shown in the top panel below. In only one High-Income country are both Rule of Law and (control of) Regime Corruption <0.5.

The bottom panel shows that these conditions are mostly found in democracies. Only in three autocratic countries are conditions of Rule of Law and Control of Corruption very strong (>0.75). Two of those countries are South-East Asian High-Income countries, Hong Kong and Singapore, while the third is an African Low-Income country; Benin, c.f. Figure 1

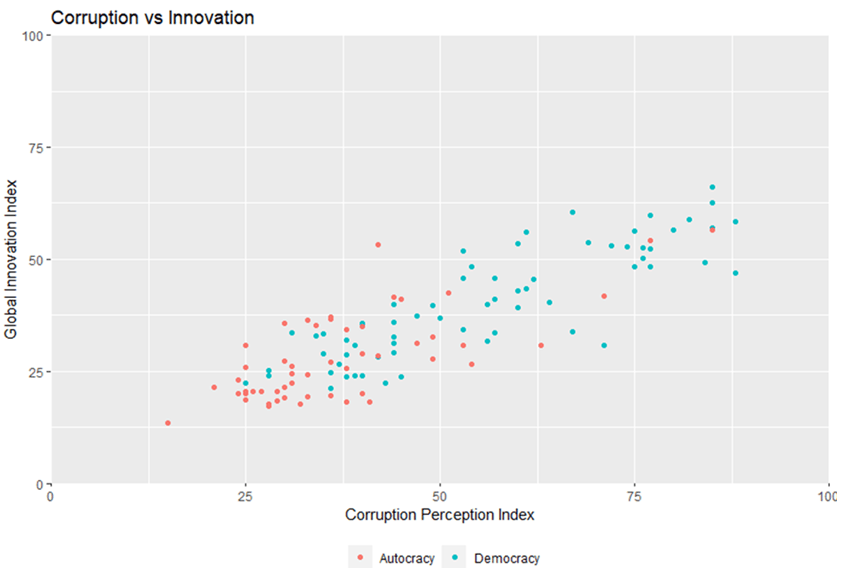

In another post,

I tried to show that democracies are better than autocracies to innovate. Below is a rather roundabout way to show this as i depicts the relationship between corruption and innovation.

One problem with my graphs is of course that the relationships between institutions, corruption, trust and growth are complex and not easily captured in a few graphs like in this post. Casual relationships are difficult to disentangle since there might be interrelationships between the variables and unknown factors not considered.

To do that, one needs to use econometric techniques that disentangle the endogenous relationships between the variables mentioned above. I am not going to do that. I swore a holy oath to myself when I retired that I would never again run even a simple regression.