This is the English version of my letter to newspapers. It was published in Göteborgs-Posten 26 November. The Swedish post there is shorter due to the newspaper editor’s demand for the post to fit within their character limit for letters. A longer version was published by Sörmlandsbygden 26 November, and in Västerbottenskuriren 1 December. Anyway.

Those who advocate reduced consumption to save the planet believe that economic growth means that more of the earth's resources must be consumed. But in many countries, GDP increases at the same time as emissions decrease, even taking into account that the production of imported goods takes place abroad. Less and less of the earth's resources are used at the same time that our production takes place through reduced emissions of carbon dioxide.

De-coupling is already here.

Source: Our World in Data

Degrowth advocates do not think it is going fast enough and want to stop rich countries from growing. However, they believe that poor countries must be allowed to grow in order to achieve our standard of living.

Then an insoluble problem arises. The rich world has the largest market for goods and services produced in poor countries. If the rich countries are to reduce their consumption, then the demand for the goods and services produced in poor countries decreases. This means lower incomes in the poor countries that could otherwise have been used for better healthcare, education and infrastructure. Lower incomes also lead to fewer investments in green technology that would have replaced the older production apparatus.

In the rich countries, reduced incomes stop public and private research and development of green technology. Reduced tax revenues mean that the countries do not have much room left after spending on education, healthcare, care for the elderly and police. Private sector investment collapses because there is no expectation of future profits.

There are some degrowth advocates who are not satisfied with us getting poorer. They also want our populations to shrink. If the above development is realized, no other measures are necessary per se. The Malthusian trap strikes again and childbearing in our countries collapses with falling incomes.

Degrowth advocates demand reduced population growth because they believe that consumption and production must be reduced to save the planet. It would be devastating for the environment in the future as a reduced population growth leads to a reduced working population. Already today, the working part of the population is decreasing in many countries. This smaller share in the population has to support an increasingly larger share in the population that is either to young or old to work.

Fewer people working is bad for the planet for two reasons. As people save more in their working age, savings in economies will decrease. It also leads to lower investments in new green technology. The future capital stock will be older, smaller and more resource-demanding than in the case of another development. In addition, weaker population growth means that there are fewer people hatching new ideas that can be realized in new production processes, goods and services that consume even less resources than today.

Downgrowth leads to a dirtier world. If, instead, continued growth with lower emissions is allowed to continue, the planet will be saved.

Other blogs about degrowth

This post was another of the posts I upload after having one of my letters published by a newspaper. These posts are often too short to give a meaningful presentation of the matter in hand. Here is a longer post touching on the subject that I wrote five years ago.

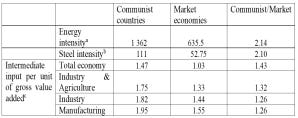

Only growth and market economies can save the planet.

Spoiler: Global warming is a real problem that needs to be addressed. However, policies appeasing the cries of alarm demanding de-growth and socialism would be disastrous for our planet. Most of the growth today is intensive. That means that we consume more of less material-intensive products such as information- and telecommunication services. The prod…

But I’m a rambling clown. If you want to read something serious about this, here are a few suggestions.

Debunking Degrowth by Justin Callais is deveoted to the subject. He shows very effectively why degrowth is bad.

Noahpinion by Noah Smith is another blog where degrowth is discussed from time to time.

Both Justin’s and Noah’s posts about degrowth discuss studies if you want to read more.

Here is a nice link to a review of degrowth studies. Spoiler. They are crap.

Inspecting the 54 studies that used qualitative or quantitative data analysis, we find that they tend to include small samples or focus on peculiar cases – for example, ten interviews with 11 respondents on the topic of local growth discourses in the small town of Alingsås, Sweden (Buhr et al. 2018), or two locations of ‘rural-urban (rurban) squatting’ in the Barcelona hills of Collserola (Cattaneo and Gavaldà 2010).

Alingsås is now known for more than having an astonishing number of cafés. I’m not sure people in Alingsås want to be associated with that ludicrous study.