Another post about wage shares, real wages and labour productivity.

Variables that might have something to do with each other.

Spoiler: The wage share in GDP remain stable while real wages increase. Real wage developments have more to do with labour productivity developments.

Now and then, some people get upset as newly released statistics appear to show that the wage share has decreased. These people, (Swedish far-lefties), get mad because that implies that profits are increasing. Since their opinions are based on emotions instead of facts, they ignore or do not understand the difference between gross and net profits.

If they did, they may have noticed that the share in depreciation has increased over time pushing the share of net profits in GDP down.

Shares in GDP 1850-2000. Percent.

Source: Historia.se from Edvinsson, R. (2005). “Growth, Accumulation and Crisis”. Note: I may have chosen a GDP measure, of several in Edvinsson, that exaggrerated the level of the wage share a bit. That is not important. The main point is that the wage share, irrespective of the GDP measure, is stable over time.

The increasing depreciation share in GDP is due to many factors. It may come about directly by increasing investments in all industries and also by increased shares of capital intensive industries in total GDP.

The same people also seem to think that a decreasing wage share means that real wages have decreased. Even though it is often the case from one year to the next, it does not follow automatically since real wages are increasing over time without any upper bound while shares of depreciation, profits and wages in value added are restricted to sum to 1.0.

The misconception about wage shares and real wages also ignore the difference between nominal and real entities. Wage shares are calculated in current prices while real wages are wages deflated by a price index. Price developments can make wage shares and real wages move in opposite directions even if nominal wages increase. Real wages increase when wages increase more than prices. At the same time, net profits can increase more than wages which yields a decreasing wage share.

Over longer periods of time though, real wages increase while the wage share is relatively stable and fluctuates around a mean.

The economy wide wage share fluctuated around 0.7 between 1850 and 2000 while the real wage increased on average by almost two percent per year.

Economy wide wage share and real wages in Sweden 1850-2000.

Source: Wage and wage share, Historia.se from Edvinsson, R. (2005). “Growth, Accumulation and Crisis”. Consumer prices.Historia.se Edvinsson, R. & Söderberg, J. “The Evolution of Swedish Consumer prices 1290-2008.” Note: I may have chosen a GDP measure, of several in Edvinsson, that exaggrerated the level of the wage share a bit. That is not important. The main point is that the wage share, irrespective of the GDP measure, is stable over time.

Real wages are more related to labour productivity. The same people that get upset about temporary declines of wage shares would hate the following reasoning if they read it. The reasoning is based on the neoclassical model. The neoclassical model posits that that labour is paid according to its marginal productivity, and the labour share equals the output elasticity of labour. The latter implies that the labour share is relatively stable since it depends on the technology.

The labour share, LS, equals total wages paid divided by the value of GDP: LS = W*L/P*Y, where W are wages, L employment, P price and Y the volume of GDP. The expression L/P*Y is of course the inverse of the marginal productivity of labour assuming a Cobb-Douglas production function. From that we can conclude that the development of real wages equals the labour share times production per hours worked, (W/P) = LS*(Y/L). Since the wage share is relatively stable over time, developments of real wages and labour productivity should move closely together.

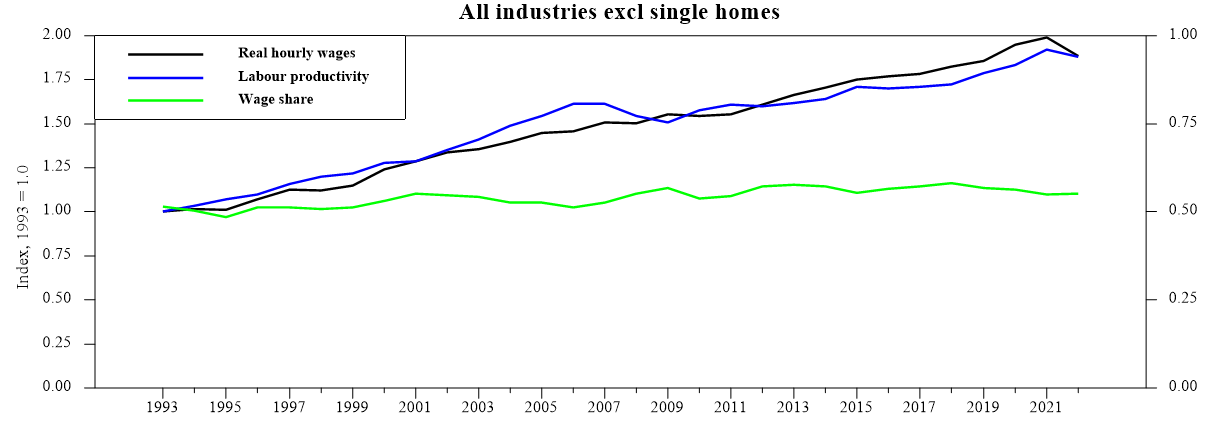

Economy wide wage share, real wages and labour productivity 1993-2000.

Source: Statistics Sweden, National Accounts.

The neoclassical model assumes perfect competion which is a strong assumption for many markets. Nevertheless, it fits data quite well for Sweden 1993-2000. In a future post, I will instead assume that imperfect competion is a better description of markets and see how that affects the relationship between real wages and labour productivity. For those that can’t wait. google decoupling of real wages and productivity.