A percentage-pointless entry

It's not only how we produce things that matter, it's also what we want to consume.

I guess that I’m not the only one who at some point in time imagined himself that he had come up with something clever. While I was using GDP per hours worked for Denmark, Finland and Sweden for another purpose, I was beginning to think that it might be interesting to decompose total GDP per hours into sectors. Such a decomposition would make it possible to see which sectors contributed the most or the least to growth of total GDP per hours worked in the three countries. And then I thought, stupidly enough, that those results would easily translate in clever policy implications. Ha!

So I embarked on the little project making all kinds of calculations before I was reminded of Paul Krugman’s piece on hot dogs and buns which you can find here.

The point made by Krugman is that the sectoral composition is a consequence of the interplay between technology and demand. First, one needs to understand that productivity growth means that incomes will grow. This higher income will, to some extent, be spent on more goods and services. Therefore, shrinking employment in sectors with high productivity growth will be matched by increasing employment in sectors with high demand for their products leaving total employment stable.

Even if you already know that the butler was the murderer, let’s have a look at how I wasted my time (and now yours). So let’s have a look at how I decomposed GDP per hours worked growth for the three countries mentioned above countries for the period 1995-2016.

In order to decompose total labour productivity into sectoral contributions, one needs to aggregate labour productivity for the different sectors. Summing the different sectors’ labour productivity will not do since labour productivity is a real entity consisting of value added in fixed prices (relative to labour input) and therefore not not additive.

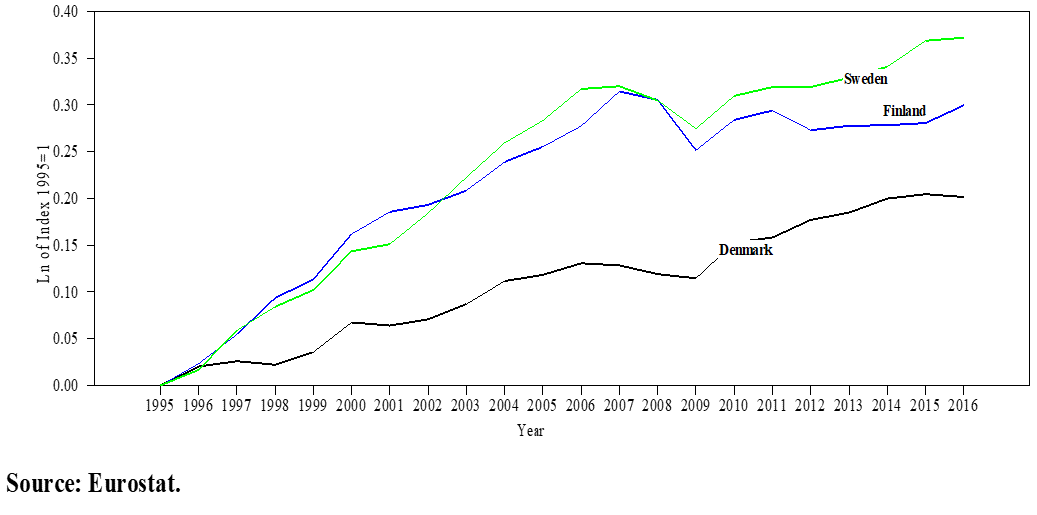

Before the decomposing exercise is undertaken, it is useful to have a picture of how total labour productivity growth developed in the three countries over the period. From 1995 to 2016, GDP per hours worked increased on average by between 1 and 1.8 percent per year in Denmark, Finland and Sweden. , c.f. Figure 1.[1] Figure 1. GDP per hours worked in Denmark, Finland and Sweden.

As noted above, total GDP is the aggregate of all sectors’ value added. Developments in individual sectors are therefore important and sectors who make up a relatively larger part of GDP have a larger impact on total GDP and total labour productivity growth per hours worked. A natural point of departure is therefore to have a look at industrial structures in the three countries. The different industries are grouped into six aggregates in order to make the analyses easier.[2]

Using these aggregates show that industrial structures in the three countries are roughly similar. Manufacturing is relatively larger in Finland and Market Services and Public Services is relatively larger in Denmark. Sweden seems to be an average of the other two countries, c.f. Table 1.

Table 1. Average sector shares of GDP 1995-2016 in Denmark, Finland and Sweden (%).

Focusing on labour productivity developments in the four largest industries show some interesting differences. Danish labour productivity growth is higher (and positive) in Construction industries and Public Services but lower in Manufacturing and Market Services than in Finland and Sweden, c.f. Figure 2. Figure 2 GDP per hours worked 1995-2016 in the four largest sectors.

I guess you're not that impressed of this. Nor is my furry friend who fell asleep.

The larger the sector and the larger its productivity growth, the stronger impact does the sector have on aggregate labour productivity growth. Between 1995 and 2016, the Manufacturing sector in the three countries grew faster than other sectors. Productivity growth in primary sectors and mining displayed the second highest growth in Denmark and Finland while Market Services claimed that position in Sweden. Considering that Market Services is the largest sector in the three countries, developments in this sector is clearly important for total productivity, c.f. Table 2.

Table 2 Average annual sectoral productivity growth 1995-2016 (%).

The importance of Market Services is particularly true for Denmark since this sector contributed by 0.84 percentage points to total labour productivity growth between 1995 and 2016. Despite displaying the highest productivity growth of all Danish sectors, Manufacturing only contributed with 0.10 percentage points, less than Public Services. Market Services accounted for the largest contributions to total labour productivity growth also in Finland and Sweden where also Manufacturing industries played larger roles than in Denmark. Together these two industries accounted for 1.36 percentage points of the average annual growth of total labour productivity in Finland. Corresponding for Sweden was 1.78 percentage points, i.e. almost all of the average annual total labour productivity growth in Sweden was due to Manufacturing and Market Services, c.f. Table 3.

Table 3 Average annual total productivity growth (%) and sectoral contributions to it (p.p) 1995-2016.

And this is where I came to the so what? conclusion. The sectoral composition in a country is the result of the interplay between technology and consumer preferences. Higher productivity growth in manufacturing reduces the number of people needed to produce its products but this is counteracted by the increased demand for services which is labour intensive. Higher productivity growth reduces a sector's relative price while an increased demand for its goods tends to increase the sector's relative price thus changing the sectors share in overall GDP while leaving overall employment stable, c.f. Figure 3.

Figure 3. Employment rates in Denmark, Finland and Sweden 1995-2016 (%).

[1] All series depicted in the figures show the log of an index, which equals 1.0 at 1995 so the series start at zero. Since the vertical axis is in log units, the slopes of the series are the rates of growth. An increase of 0.1 is a growth of 100*(exp(0.1)-1).

[2] All industry data is in practice aggregated. For the purpose of this entry, twenty industry aggregates on the “first-digit” level were downloaded from Eurostat. See Annex 1 for an overview of the aggregates and the individual industries that make up the aggregates.